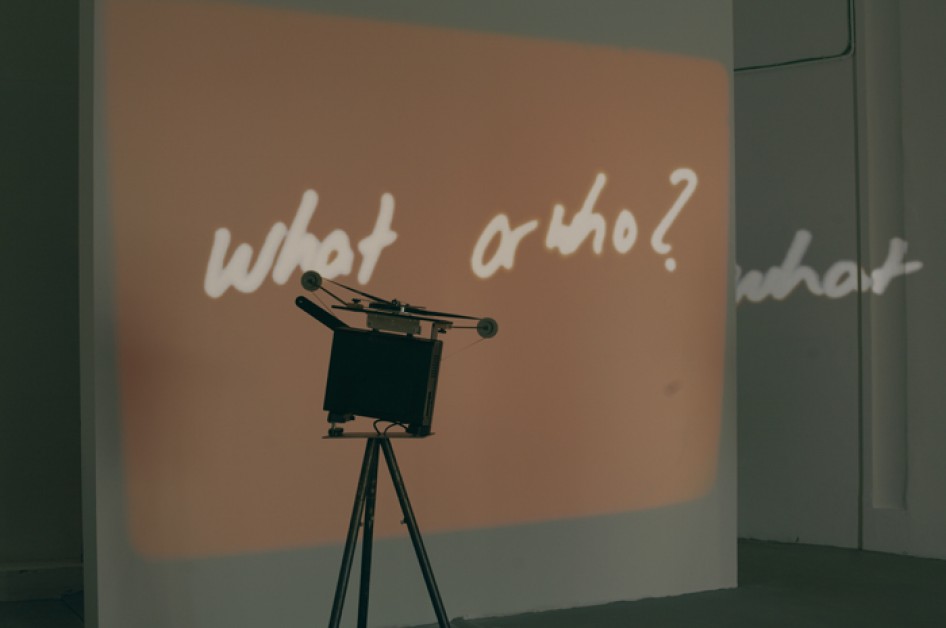

Timothée Chaillou: Talking aboutCoro Spezzato: The Future Lasts One Day(2009), you once said that ‘the installation consists of five 16mm projectors forming a chorus. The idea behind the installation is the Venetian polychoral style of the late Renaissance and early Baroque – a type of music involving spatially separate choirs singing alternately at a time when the theocentric construction of the world was slowly being replaced by a humanistic idea of reality and choirs were allowed to sing about ideas as well. The lyrics, projected as fragments of text, make a statement about the future and analyze the status quo through a multitude of voices. The projectors are co-ordinated with each other and speed up or slow down according to the text. They follow a choreographed order by capturing a moment of reformation and translating it into silent choreography… the projectors create a “humming” sound as they slow down and speed up.’

Rosa Barba:The piece is a staged performance. The lyrics begin to make sense once you’ve experienced the piece for a while. Then the viewer starts to make connections and gradually understand the piece as a single collective voice. The words themselves are like signs on the wall, indicating directions. Once played together they become a formation. The viewer becomes a ‘live-editor’ as a kind of story is created while being performed in its own choreography. And yes, the idea is derived from the polychoral styles you mention.

Timothée Chaillou: Why the nameCoro Spezzato? What is metaphorically broken? Or what is really broken?

Rosa Barba:Coro Spezzato is a name invented for a choir in Venice during the Renaissance. It’s called ‘broken’ as it does not work like a classical choir, the choir is spatially fragmented. The different voices have broken rhythms; they react to each other with questions and answers.

Timothée Chaillou: Did you write the lyrics for Coro Spezzato?

Rosa Barba:I took some original lyrics as a starting-point, describing a situation in terms of the present and possible future. I translated this into our times, into a form of statement.

Timothée Chaillou: Is it an opera or a drama?

Rosa Barba:It’s fiction.

Timothée Chaillou: Does the installation recall a magic lantern, in that each word sheds ‘a little light’?

Rosa Barba:Yes, little thoughts – expressed with light.

Timothée Chaillou: Does the fading colour of the projected words reflect nostalgia?

Rosa Barba:No, this is only part of my filming process. I gave some words a kind of visual punctuation.

Timothée Chaillou: Do you think you are using obsolete technology with your old projectors? Why did you choose to work with film instead of video?

Rosa Barba:No technology is obsolete as far as I am concerned. Film is a medium that has qualities you can’t replace. It always has a perform-oriented character which I include in my installations. Nostalgia is something that reminds you of the past and cannot be repeated. As it is a photographic process, film has a special presence for me with great potential for storing memories and history. I never use rediscovered footage in my film installations. My films are made out of new ideas. They’re anchored in the present, and relate closely to the possibility of light in images – which cannot be produced by video. So I don’t think my pieces have anything to do with nostalgia.

Timothée Chaillou: Do you use old projectors as a stand against new technology? Why are you interested in these kinds of ‘bodies’ which ‘speak/talk’ with images?

Rosa Barba:I’m interested in the ‘structuralism’ of film. Each component – like ‘sound,’ image, text and material – has its own character and can be removed or reinforced or exist on its own. This is not really possible with video where all the components are merged and translated into digital codes. For example, the sound on a film is like a drawing or a sign added to the material. There are all these little ‘worlds’ that create a universe. I’m interested in this subtle interrogation into – and co-optation of – industrial cinema-as-subject via various kinds of what might be called ‘stagings’ – of ‘the local’, the non-actor, gesture, genre, information, expertise and authority, the mundane – removed from the social reality within which they were observed and which qualifies them as components of the work – to be framed, redesigned and represented. The effect of this contests and recasts truth and fiction, myth and reality, metaphor and material to a disorientating degree, ultimately extending into a conceptual practice that also recasts the viewer’s own staging as an act of radical and exhilarating reversal – from being the receiver of an image (a subject of control) to being in and amongst its engine room(s), looking out.

Timothée Chaillou: Is a projector a podium for images?

Rosa Barba:It’s the images’ body.

Timothée Chaillou: Are you tempted to create a ‘sort of imageless cinema’?

Rosa Barba:Yes, a large part of my research involves work on this. But it also involves creating an orchestrated, spatial cinema.

Timothée Chaillou: It’s often claimed that movies or videos engage issues of temporality. I think this is too restrictive and neglects other aspects of movies such as movement, materiality of the image, and the films themselves.

Rosa Barba:I’m preoccupied by the immanent aspects of film: how the projectors function, the perception in space, the materiality of the medium itself – not just optically speaking but in its materiality, in sound and time. I’m also interested in an image’s haphazard and psychic dimensions; the speculative narrative that conjures up invisible landscapes…landscapes with unseen histories, sometimes even pure text-landscapes.

Timothée Chaillou: Are you attracted by movies in which we can see the technical material?

Rosa Barba:Not really.

Timothée Chaillou: You’ve said that you are more interested in texts about cinema than cinema itself. Do you share this idea with anybody else?

Rosa Barba:In a nutshell – Giordano Bruni, when he writes that ‘the Observer is always at the centre of things.’

Timothée Chaillou: Was it ‘a two-dimensional analogy or a metaphor’?

Rosa Barba:I was thinking about this title while working on my exhibition at the Art Centre in Vassivière, especially as regards White Museum, which involved projecting white films on to Lac Vassivière – a huge artificial lake under which a village was submersed in the 1950s. I was thinking about the fiction that lies under the lake’s surface which I turned into a screen – a two-dimensional screen… although the lake actually inhabits a whole three-dimensional world which I enacted by facing the film light on to it. So, through the cinematographic process, the lake turned into a metaphor for historic revelation.

This text is an extract from the interview published in Annual Art Magazine Issue 5.