One of my college friends introduced me to The Smiths at the end of March 1984. She had gone to London for spring break. During her trip, she walked into a record store and asked for something typically English, something that everyone was listening to. The clerk handed her a copy of the first album by The Smiths, which had been released a month before. Upon her return, she lent me her copy of The Smiths, and within twenty-four hours, I had my own.

As I listened to the first song on the album, “Reel Around the Fountain,” I wasn’t aware that this was the last record that would, as the saying goes, change my life. There is a limited window of time when this sort of thing can happen to a person. For me, it was roughly the period from 1974 to 1984, not a bad time to be coming of age, considering the deplorable state of pop music in subsequent years. I suppose this opinion is hard to defend, but there lies the problem of making any claims at all about pop music. Often people who love it are searching for themselves, or more likely, an ideal version of themselves, in what they hear.

I understood very little of what I was hearing at first. The music, sounding simultaneously modern and old-fashioned, couldn’t have been more different from the dominant trend of the preceding years, manufactured pop groups playing electronic music. The Smiths were a traditional four-piece rock band, distinguished by the incandescent talent of guitarist Johnny Marr, who also composed the music. The words, full in equal measure of yearning and resentment, were written and sung by a character named Morrissey. The beautiful music seemed timeless, but the mournful tone of Morrissey’s voice, languid and occasionally maniacal, seemed exactly right for the times.

The only word I can use to describe the early 1980s is a favorite of Morrissey’s: vile. The economic decline that had begun during my childhood showed no signs of reversing itself, though some people were getting very rich. In public life, an atmosphere of meanness and gratuitous cruelty came to appear normal, and more sensitive souls turned inward. A group of shy, isolated young people retreated to the only place their voices had any effect – their bedrooms – and for many of them, The Smiths provided the perfect theme music to accompany their private dramas.

In my youth, I had the habit of buying records for their covers. Before the internet made a wide variety of music available even to kids in the provinces, there were few alternatives. The cover artwork was often a reasonable way to gauge the merits of a record that got no radio airplay, that is to say, a record that might actually be worth buying. I had noticed the first single by The Smiths, “Hand in Glove,” in a record store near where I lived. The cover features a picture by Jim French, a rear view of an anonymous nude man. The sentiments of the photographer seemed fairly unambiguous, and I was afraid to buy something that made such a blatant statement.

The Smiths, the album that followed this single, bears a cover image of Joe Dallesandro’s torso as it appeared in Flesh, produced by Andy Warhol. I had seen this movie. It was the first feature directed by Paul Morrissey, no relation to the singer, but the coincidence led me to take the image on the cover as a clue to the album’s contents. Flesh presents a day in the life of a male hustler. He is a beautifully proportioned example of trade. He has a wife and child, but most of his customers are men. He interacts with a number of Warholian types – aggressive women, desperate johns, fellow hustlers, tattered drag queens – but he remains rather passive throughout the film. Flesh is a comedy; everyone is on the make, and sex is a joke.

The Smiths’ first album suggests the world of a working class youth with a taste for revenge. There is no role for him to play in the industrial wasteland where he was raised, so he writes his own story. He assumes poses that will be useful when fame and fortune beckon. He tries to avoid being beaten up or ground down. He wants to relive the old school days, this time with a sense of mastery. He relies on the favors of older men and ultimately resents the situation, or perhaps he only fantasizes about it. He rejects the advances of well-meaning female friends. He falls into the abyss of unrequited passion. A sense of menace pervades the scene, but the action remains unconsummated.

These impressions occurred to me before I had read any publicity about The Smiths. Such was the work of Morrissey’s words on a young, impressionable mind. I bought this album decades ago, but my original memories of it are still vivid.

I must confess that the spell did not last. I bought and enjoyed Morrissey’s early solo albums, Viva Hateand Bona Drag, and in them I found consolation during an especially lonely period of my life. Then came Kill Uncle in 1991. I never bought that album, and my ignorance of what followed in the next ten years of Morrissey’s career was complete. I missed a number of his solo albums, some of them better than others; Morrissey’s array of problems and provocations, fascinating to members of the music press, at least for a while; a change in record labels, and after disappointing sales, no record label at all; finally, the move to Los Angeles. Morrissey in exile simply slipped from view. Widely dismissed as a has-been, Morrissey remained a star to hardcore fans who followed his every move and paid tribute to him in ways barely noticed by the media.

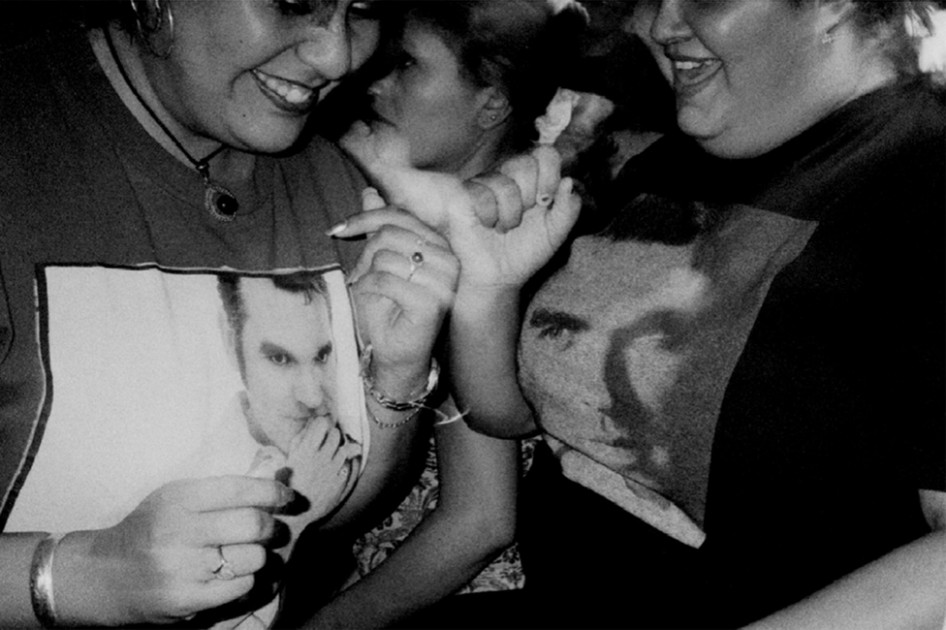

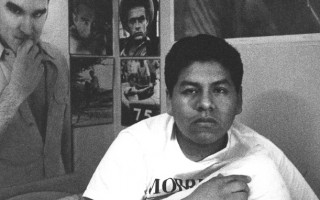

In November of 2001, I saw an advertisement for a club in Los Angeles called London Is Dead, which exclusively played Morrissey and Smiths music, and I thought to myself, I’ve got to see this. It was a surprise for a lot of reasons. At the event, I was surrounded by people in their twenties, dancing and singing along to music I had loved long ago. The atmosphere was quite joyous, and belied the popular perception of Morrissey as a poet of doom and gloom. Another surprise was that most of the crowd was Latino. A whole scene had developed around the work of an artist who hadn’t released a record in several years. I was happy that my original opinion of this music was being confirmed, and more importantly, I felt that I had something in common with a group of young people to whom I would not normally be expected to have a connection. I decided that night to document the scene.

When Morrissey asked the crowd at one of his shows at the Wiltern Theater in Los Angeles, “How are things in San Bernardino?” he was doing more than making idle chatter. He was acknowledging the geography of his grassroots audience. During the hiatus of Morrissey’s career, the region where his fame was the greatest stretched from East Los Angeles, Boyle Heights, and Highland Park in the west to San Bernardino and Riverside in the east. This corridor along the 10 and 60 Freeways is the eastern edge of the Los Angeles metropolis, formerly irrigated agricultural land, then a center of heavy industry, now old and new suburbs.

Unlike the Pacific coast or the Hollywood Hills, this region is rarely chosen to represent Southern California in movies or television programs, perhaps because it offers a better sense of what it is actually like to live in the region. There is a lot of pollution, traffic is terrible, and real estate is more affordable the farther east one travels. Most of the population is Latino, and several cities have Asian majorities. The outlying area of the region is called the Inland Empire, but its boundaries are vague and there is no emperor. Audiences all over the world have seen images of Southern California in the television shows Beverly Hills 90210 or The O. C., but the true hotbed of youth culture is more likely to be Pomona 91766 or The I. E.

This begs the question, Why is Morrissey so popular with a Latino audience? While there are almost as many answers to this question as there are fans, I noticed some patterns in the conversations I had while documenting the scene. Some insist that what has been called a phenomenon is only a coincidence or an example of media hype, but I would say that it is indicative of wider changes taking place in youth culture. Although I concentrated on the metropolitan area of Los Angeles, I also attended fan events and concerts in Tijuana and El Paso, and I suspect I could have photographed scenes in any number of other cities, particularly in the American Southwest. Before the “Latino Morrissey fan” is relegated to a marketing profile used to shift a few more units of obscure items in monopoly capital’s back catalog, I will mention some of the things I learned in the course of my project.

At least since the 1970s, there has been a significant current of Anglophilia in the Los Angeles music scene, and not just because the area is a popular tax exile destination. The Smiths were played on mass-market radio in Los Angeles – unlike every other major U. S. city – and they are very much alive in the popular memory. The Anglophile tradition continued with ex-Sex Pistol Steve Jones’s immensely popular noontime radio show Jonesy’s Jukebox, which provided Angelenos with daily doses of Northern Soul, Glam Rock, Ska, Reggae, and of course, Punk.

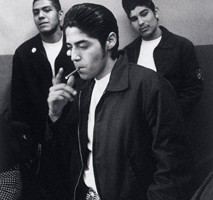

A demographic change has occurred in Los Angeles, and strictly in terms of numbers, Latino culture is (or soon will be) the dominant youth culture in the city. What form this culture will take is an open question. The combination of new demographics and old Anglophilia has some surprising consequences; for instance, anyone walking around Hollywood wearing a Union Jack on his jacket is almost certain to have a Spanish surname.

A sense of historical continuity is also an important aspect of the phenomenon. Among Chicanos who were born in Southern California, “oldies” music (e. g., Doo-Wop, American Soul and R & B) has been revered for generations, and the most recent generation has embraced the music of the Punk and post-Punk eras in its turn.

The phenomenon expresses itself somewhat differently among the children of immigrants. Though they may speak Spanish at home, they don’t necessarily feel a connection to Spanish language pop music. At the same time, the themes associated with a lot of great English pop music – especially sexual ambiguity and contempt for middle class respectability – speak volumes to them. A rebellion against conformity and traditional machismoenacted in a language poorly understood by parental figures proves irresistible.

The members of The Smiths were all sons of immigrants, and while Morrissey does not refer to this fact directly in his lyrics, the songs have a pervasive mood that strikes a chord with the children and grandchildren of immigrants. A line like, “I just can’t find my place in this world” (from “Ouija Board, Ouija Board”) is profoundly meaningful to this new generation of fans, though in ways that Morrissey could not have originally predicted.

Recently, Morrissey has capitalized on these cultural affinities. Some of his songs acknowledge a Latino audience, and his stage presentation would not be out of place on Mexican television. Latin American culture has traditionally had plenty of room for crooners belting out highly dramatic songs, and Morrissey seems to fit right in.

Many English pop stars are aware of the adoration they inspire among U. S. Latinos, but to my knowledge, Morrissey was the first one to change his image in an effort to cultivate this audience. The effect is appropriatelyrecherché, and I sometimes find myself wondering if he will one day take his act to Las Vegas. I think that this may well be a case in which Morrissey, while appearing to be mired in nostalgia, is actually catching a wave of the future.

Although there were moments when world domination seemed imminent, The Smiths and Morrissey never quite captured a mass audience. They have never been as famous as their gifts clearly indicated they could be. Even so, I still find it hard to believe that some people simply have no idea who they are. Others, left with a superficial impression of miserabilism or even self-loathing, know The Smiths but reject them. There seems to be little common ground on the subject, and conversations between fans and non-fans lead to the sort of irrational, emotionally fraught impasses usually experienced in discussions of religious dogma or sporting events.

I think that a crucial factor in the case of The Smiths is the complexity of the world they suggest. Their approach has an aura of self-deprecation, but this only serves to intensify the power of their seduction. The Smiths never appeared on their record covers. Their stand-ins were a series of “cover stars,” often figures from English popular culture of the 1960s. Many fans, especially young Americans, find themselves researching who these people were, and thence are led down the path of true obsession. The world of The Smiths offers such a wealth of detail that a listener can get lost in it, just as a reader gets lost in his favorite novel.

The character of the box bedroom rebel, who made a cameo appearance in the Dickensian novel of Thatcher’s Britain, has reappeared in sunny California. This turn of events isn’t as strange as it seems. Wherever there are working class kids attempting to flee their suffocating families, yet incapable of leaving them behind, this figure will return. Morrissey described his favorite characters in movies as “people with their tails trapped in the door… trying to get out, trying to get on, trying to be somebody, trying to be seen” but held back by family expectations, old bonds of friendship, or simple lack of money. Many young people see themselves in this description, and they flock to Morrissey for moments of solace and imaginary escape.

My most intense memories of The Smiths are of their early work, a handful of singles and the debut album. They contain the last lyrics that Morrissey wrote before he knew he would be famous. In a sense, he spent his whole life up to that point preparing his material for a breathless, and by no means certain, bid for immortality. After that, Morrissey’s lyrics became more indirect and vague. Later still, Morrissey’s solo material resorted to self-conscious camp a lot more than The Smiths ever did, and the threat of self-parody loomed.

Throughout his career, Morrissey has written succinct word portraits of types resurrected from the “kitchen sink” realist films produced during his childhood. In England, he mourned the disintegration of traditional working class culture, but when he moved to Los Angeles, he discovered aspects of this culture reinvented in a new landscape. The persona narrating his songs was originally that of a working class youth ambivalent about being admired by his betters, and it gradually became that of the older, successful man doing the admiring. This transition, partly artistic, partly geographic, and accomplished over nearly two decades, is interesting in itself, but I would still maintain that Morrissey’s first, most urgent utterances were his greatest.

In my initial flush of adoration for The Smiths, I imagined an army of fans making their presence felt in a hostile world. Effeminate, bookish, incapable of sustaining gainful employment or of starting families of their own, they were disappointments to their fathers. But what made them failures in a conventional way of life made them splendidly successful in another realm of endeavor. They were modern dandies. They rarely banded together, but one can sometimes catch a glimpse of them in old concert footage.

A whole new generation of dandies has appeared to worship Morrissey, though the scene and its forms of expression have drastically changed. One thing remains constant: the people I met and befriended do what they do not because someone told them to buy a record or to go to a concert, but out of love and spontaneous enthusiasm. The events I attended were not planned or staged by publicists. They were organized by the fans themselves. They were expressions of popular culture in the truest and most admirable sense. It’s important to remember that the early Smiths records were released by an independent label with very little money for promotion. The band’s success was a surprising departure from business as usual, and a story unlikely to be repeated in a music industry dominated by a small handful of corporations.

While I was documenting the fan scene, Morrissey made a comeback – or should I say a return? – and an apparatus of publicity made it possible for him to reach a wide audience. He appeared on television and radio, and in countless magazines. He was described by the meaningless hyperbole and impoverished adjectives that are the stock in trade of mass culture. Morrissey went from being a fanatical cult’s object of worship to being just another celebrity. Among the fans, there was excitement about this development, but there was also the sense of an ending. The scene that was faithful to Morrissey during his period of relative obscurity continued to exist, but it just wasn’t the same. I loved the homemade quality of the events and the complete conviction of the people who attended them. An era has passed, but I can say I was there while it lasted, and I recorded some of what I saw.

This text is a condensed version of an essay originally published in Is It Really So Strange? (Los Angeles: David Kordansky Gallery, 2006).