Conversation between Rodrigo Arteaga, Raisa Bosich and Pablo Rodríguez

Wednesday February 17th, 2016

In the context of the exhibition “Against a conspiracy of invisibilities” I was invited to curate, that will take place the 28th of April 2016 at Sobering Galerie, I have selected 12 artists from Chile, who are about my age, I was born in Chile in 1988, so they are my peers. Raisa Bosich and Pablo Rodríguez are invited to be part of the exhibition and I invited them to talk about the selection and to discuss the content of the works.

PR: First I would like to know what originates the interest from the Gallery to invite Chilean artists, or what is the relationship the gallery had with Chilean art ?

RA: It started during a conversation we had with Patricia Kishishian, Sobering Gallery Director, during the process of installing a solo exhibition I did on May 2015. We had just started working together and she was very interested in learning a bit more about Chile, so she asked me lots of questions. And so I showed her the work of some artists I know, I think she was interested in what I showed her. She offered me to curate an exhibition at the Gallery as a way of learning more about Chilean Art, and I accepted because I think it is a very exciting challenge. So the birth of this project is linked to her open-mindedness in a way and her curiosity to know more about Chile and the artists I showed her.

PR: I think this is very interesting, how she might have seen something visually clear between our works.

RA: I think there is certainly an identity in Chile, which is for us very hard to realize because we are inside it.

PR: I know, she must be an interesting person, Chile obviously must be like the most exotic thing yet while seeing the works she might have been able to recognize a clear line to say “ok, let´s do this”.

RA: It is an act of trust in a way. The idea starts from her, from her openness to discover another reality that is different from hers and that I think is very peculiar. Most of the time we say that there is a deficiency in Chile in cultural terms, it’s a lack of cultural industry maybe, but it has a rather strange positive effect on the actual works which are made, not on the ability to keep doing them of course. I went to Paris and saw the excellent quality of the museums, galleries, collections, etc. and I was very surprised by the fact that the gallery was still interested in my work, you know?

PR: I know, everything is linked to a context in a way but I also think that here we have a particular relation to things, with objects particularly because of our history.

RA: We are not geographically an island but almost, the “Andes Mountain Range” separates us geographically from the rest of the world, but now of course there´s Internet, which is very important and maybe one of the most distinctive aspects of our generation if we compare it with the ones before. In most cases while I was working with the artists on this exhibition I tried to be very open to suggestions. As an artist I appreciate to have freedom to work, and if someone has an idea and that idea evolves and changes it’s perfect, because it’s a process.

PR: And because you trust that there is something with them, and you trust them.

RA: Yes, I began to ask myself: What do I really want to show? And in most cases what I truly wanted to show is what the artists want to show, you guys, you know? With many I proposed like “I am interested in this work of yours” but if they had any other suggestions I tried to listen to them. It is like a chain of acts of trust. When I was gathering all the information of the artists I invited I realized that most of them have websites and it’s something peculiar I think about our generation.

PR: I think that there is something of a “natural selection” here, that you have to stay afloat as you can, if you where a plant you’d have to grab the light otherwise it can really make you sink.

RB: I know, we have to do a bit of everything, we all build our websites, edit our own photos, take our own photos of the works, install, you are like your own producer, I feel that you spend half of the time on those things and the other actually making your work.

RA: And there are very different roles from one to another, even the role of the gallerist. We have to be gallerists as well as curators, data managers, photographers, designers, assistant, everything. I tried to think in broad terms, how do I embrace the infinite complexity of Chilean Art? From my generation, or my peers who are much more than 12 artists, in that sense it is difficult to come up with a definitive list, because maybe every list would have been insufficient in a way. It’s like making a map of something, you also talk about yourself in it. I have to say that I feel very represented by these artists. And with their works I tried to understand that each process is dynamic and that ideas change, I don’t believe in closed processes that much.

PR: Obviously.

RA: Like when it draws out conclusions, you know? I like when there are more questions than answers.

PR: So in many cases it is their most recent work.

RA: In most cases.

PR: I feel that in Chile it’s impressive how much geography impacts us, you know? As if everyone ends up talking about the landscape, through his or her work. It is the great theme that crosses different ones of course but it’s the one behind. And I feel that it is very unconscious, that you never loose the “Andes Mountain Range”, I close my eyes and I still know where it is.

RB: Not everybody, I don’t know where it is.

(Laughs)

RA: I think it is a great subject.

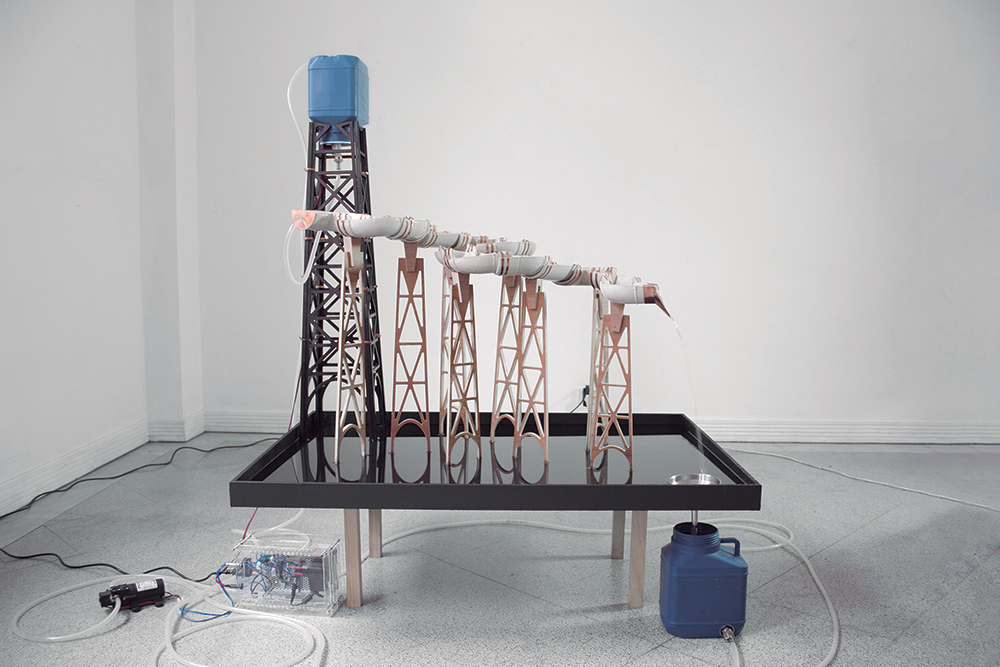

PR: We have a kind of a “landscapist” relation to objects, it’s almost like caring and loving objects, you know? Almost like to give them human qualities.

RA: It is something distinguishing I think, well I haven’t lived in other times to be able to compare them, but I see a very thoughtful process, very cerebral, but also very preoccupied with form and visual language. What I see among these artists is maybe a fine balance between idea and materiality, not losing attention on either one or the other.

PR: Maybe it’s a proximity to nature that finally makes us almost come to love objects, an affective quality, almost baroque.

RA: Like with internet, with Instagram, when we went to Art School there was already internet, there was Flickr, you could already be aware of what was being made all around the world, but in College itself the mediums for spreading visual knowledge was through photocopies of books, and even the photocopy of the photocopy.

RB: Or the slides.

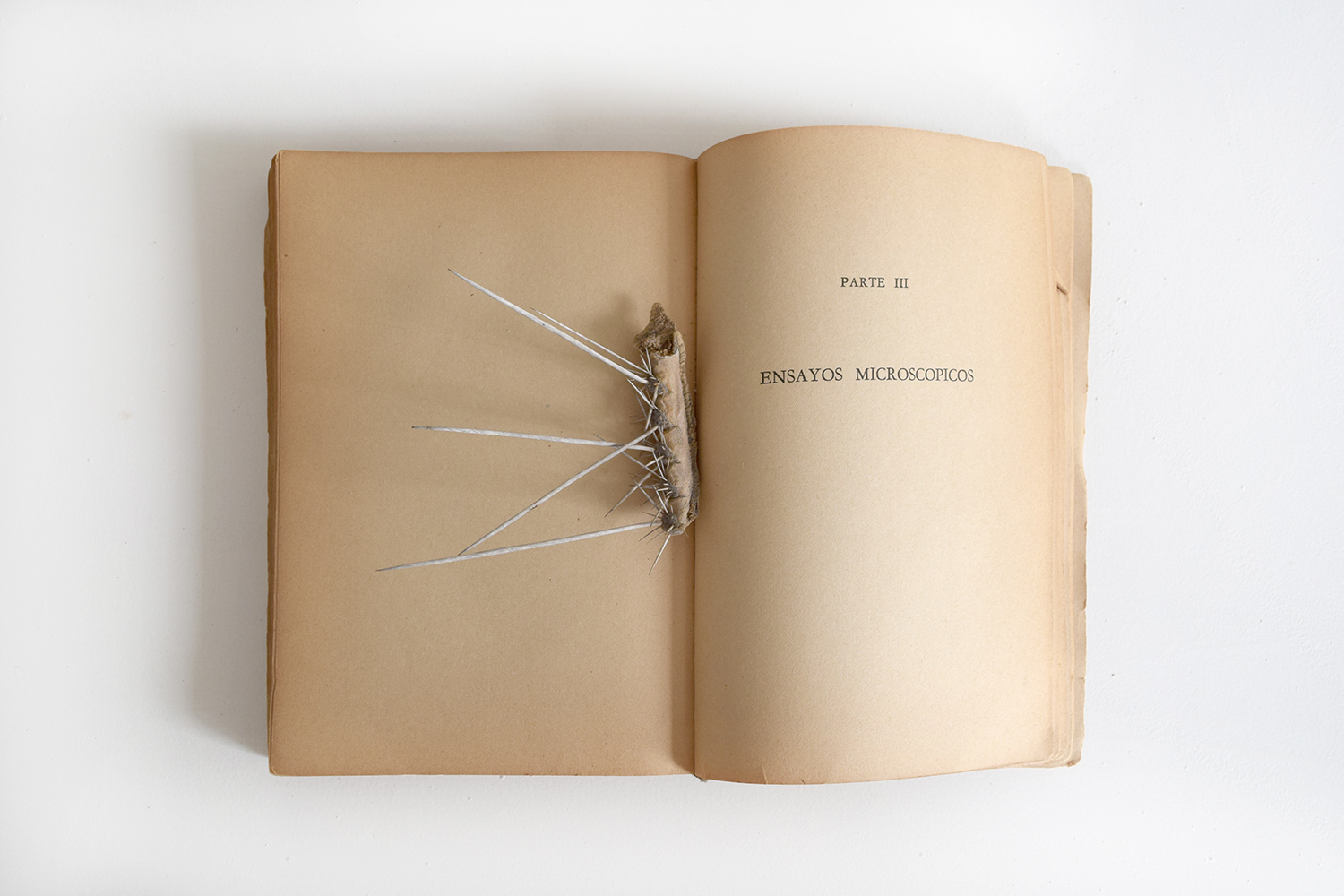

RA: The slides, full of fungi…

RB: I was thinking about what you said about effectiveness and I think it has to do with references; I cannot easily make a reference to art history because it can’t be seen here easily. In Europe, when I went and saw all the museums and understood that you could really relate to art history in a different way because of having the actual works, here it’s like you don’t have much to hold on to, you do have a specific art history but for example if you go to the museum of Fine Arts in Chile, the collection is pretty weird, it’s mostly made out of copies, it has some paintings from Chilean artists who made camels, or things they never actually saw. Like a message travelling from one to the other and to the other and that here it turned out to be quite strange.

PR: Like modernity, in a way, never happened here because what actually came was a copy.

RB: That is interesting because in Art School you have all this imagination, that you were explained of what art history is, but what you do is to really imagine it.

RA: You idealize it. It is not the same to see an image of a painting than to see the actual painting. Maybe this is what makes us very affected when we actually get to see it.

PR: In your case Raisa it’s also a very affective thing, a certain warmness that I was talking about.

RA: It is a way of knowing actually, as you are truly able to understand only what you love, if you don’t love something you are not able to fully understand it, or to enter in detail into a complex system. You are not able to access to the degree that allows you to understand it if you don’t love it.

RB: That happens to me also the other way around, when I see a work that I don’t like very much is because I am suspicious if that is really what moves them. Like when you are trapped into something and your relationship with it is not that free.

RA: Not that honest?

PR: I know, it can be noticed. That is what I feel that local art has, very deeply, like a link to your work because it’s all you have or something. And when Raisa instead of doing her work has to make a budget, to apply for funding, buy the materials she needs, and so when she receives her piece she completely indulges herself.

RA: And maybe it happens also with institutions. There is a certain enthusiasm for independent and emerging spaces, and to separate it from the “official”, but what I think is curious is that many “official” spaces are as independent as the others, as self-managed and emerging as the others, so finally it’s not that different actually.

PR: In a smaller scale the artist invests everything and is involved in every step, with institutions is maybe the same but on another scale and maybe this is why it is difficult to see funny art in Chile.

RB: I think that there is a lot, there is a tendency and everything but they are not well known.

PR: But for different reasons it is closed to certain discourses that are considered as unimportant, so it is in general more serious.

RA: We come just after a very serious generation, because of the dictatorship. Our direct teachers directly lived the trauma of the dictatorship.

RB: That somehow forced art to become totally closed and hermetic, otherwise you could actually be shot.

RA: Now I think that there is certainly a lack of infrastructure around art but that also makes the works really honest somehow, I don’t mean that in other places they are not honest but if everything actually worked, there would be much more artists. There is certainly persistence, a very strong insistence in the work, you have to really love what you are doing in order to survive.

RB: I think that you are constantly questioning yourself about all the efforts you have to make and maybe in other places you don’t even have to question it so much because it is obvious that it is possible to be an artist.

RA: Sure, it’s more accepted, even important.

PR: It’s a certain affective personal poetry that you have with your work, that the only thing that will save you; obviously if you want to make lots of money don’t be an artist, that doesn´t exist in Chile.

RA: That’s one of the things that makes it interesting perhaps.

PR: Sure, I think it is important to be aware of the local scale in a way, which is not too much affected by the rest of the world, to enhance its uniqueness. I appreciate when artists suddenly come to art but from a totally different background. I find this very interesting.

RA: From all the artists I chose, most of them deal with other areas of thought or things outside art, because of course life is always going to be more important than art. Whether it is biology, hydrography, mythology, politics, history, landscape, urbanism, poetry, etc. I feel I have learned a lot with this exhibition. I found out that I don’t have an urge to speak about certain themes that I am preoccupied with, my own theoretical concerns I try to deal with in my own work, I am continuously learning and delving in them, so I am not really interested in finding the artist who exactly says what I want to say. So I have tried to be open, not to pick just intuitively because I do believe it is intuitive to make a list and everything, but to give in if someone really wants to say something that is also what I want to stand for.

PR: Maybe it is because you have the approach of being an artist and not a curator.

RA: Sure, and it’s also about admiration, I deeply admire the artists I invited so in a sense, who am I to impose my ideas? Maybe it’s humbleness, I don’t know.

RB: I think this is an interesting chance to see a show organized by an artist who is not trying to overcome ideas over works, because sometimes in exhibitions, the works are enhanced only because they relate to the subject. Maybe because you have the freedom to relate them that way, of course you still have your own specific concerns, but it’s interesting to see that approach.